February 24 - March 17, 2012

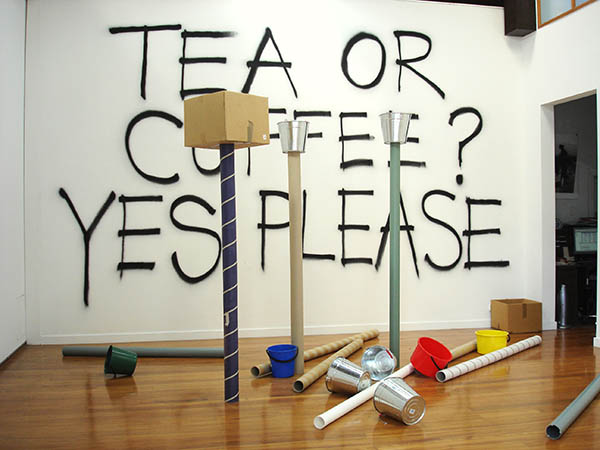

"The artists appears to have laid out a series of practical jokes…..There is the bucket on a pole following on from that same youthful prank of the bucket on the door; these works were exhibited at SOFA Gallery and First Draft in Sydney; I'm informed that the bucket has contained a variety of substances on various outings from flour and water…..and invariably the bucket and its contents are scattered over the gallery floor…..Frustrating peoples expectations with a bit of comic relief, old fashioned slapstick has its origins way back, lets not go there, other than to say that Duchamp and Picabia were a good comic duo, one tall and slim the other short and chubby.

"The artists appears to have laid out a series of practical jokes…..There is the bucket on a pole following on from that same youthful prank of the bucket on the door; these works were exhibited at SOFA Gallery and First Draft in Sydney; I'm informed that the bucket has contained a variety of substances on various outings from flour and water…..and invariably the bucket and its contents are scattered over the gallery floor…..Frustrating peoples expectations with a bit of comic relief, old fashioned slapstick has its origins way back, lets not go there, other than to say that Duchamp and Picabia were a good comic duo, one tall and slim the other short and chubby.

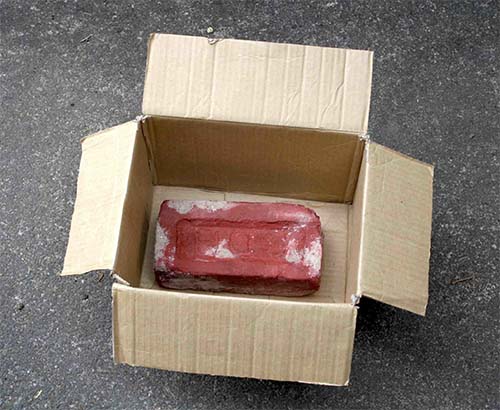

Then there are the bricks sitting around…..generally getting in the way, asking to be picked-up, but again they are not quite what they seem. They seem to work well as mates, one hollow the other a dead weight caste of lead, again duping the unsuspecting into the artist's gag.

Then there are the bricks sitting around…..generally getting in the way, asking to be picked-up, but again they are not quite what they seem. They seem to work well as mates, one hollow the other a dead weight caste of lead, again duping the unsuspecting into the artist's gag.  The lead brick weighs 18kg and I can only lift it with two hands. Of course the hollow brick smelling of perfume has the opposite effect…..The obstinate quality of the brick is partly what aids in the deception and the fact they have been painted in a way that they look like a regular brick. The artist has caste his initials into the brick much like a regular found brick, which usually has the maker's name inset into the top surface. Bricks are one of those objects that seem to be everywhere, particularly in the artist's hometown of Christchurch…..

The lead brick weighs 18kg and I can only lift it with two hands. Of course the hollow brick smelling of perfume has the opposite effect…..The obstinate quality of the brick is partly what aids in the deception and the fact they have been painted in a way that they look like a regular brick. The artist has caste his initials into the brick much like a regular found brick, which usually has the maker's name inset into the top surface. Bricks are one of those objects that seem to be everywhere, particularly in the artist's hometown of Christchurch….. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

List of works:

Buckets & Boxes on Poles, 2012

variable mixed media installation

single pole all weather option

Bricks, 2012

cast lead, brick dust, cinnamon, polystyrene

1-18kg

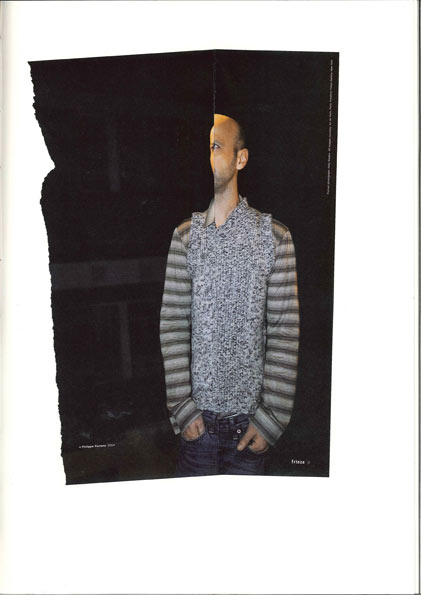

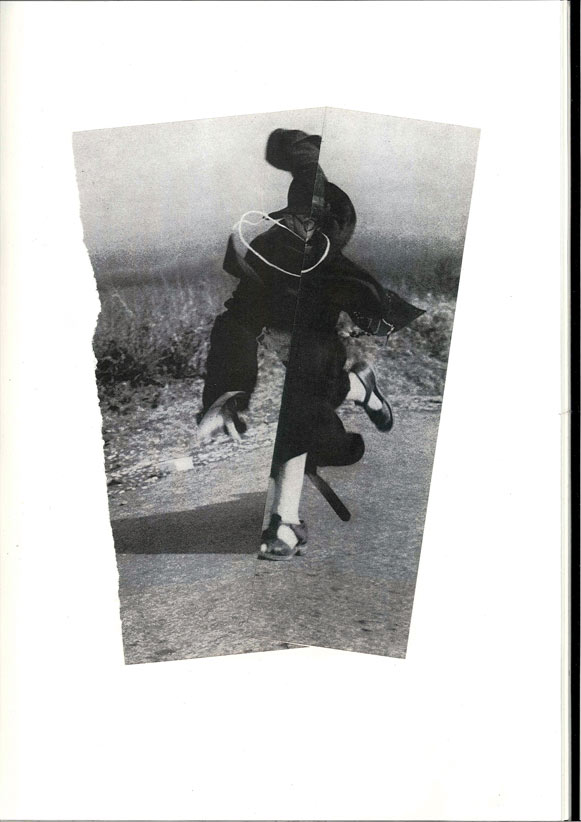

The Year of the Cyclops, 2012

folded collages, 1/1

670 x 500mm framed

The Year of the Cyclops, 2012

scanned collages, 1/3, unframed

dimensions variable

The essay below is Andrew Paul Wood's contribution to "Dumb & Dumber", a critical response to Hood's exhibition, delivered alongside Hamish Win at Jonathan Smart Gallery on Saturday 3rd March.

"Robert Hood's Who Laugh's Last?, is like most of his installations, a joke. The best kind of joke - one both simple and cosmic. Hood's works is fundamentally anchored in the meaningless and existential absurdity of human life.

The famous Marx Brothers' quote "Coffee or Tea? Yes please", casually graffitoed on the wall, is no mere throwaway line. The Marx Brothers were no intellectual lightweights - it is an absurd non-answer to a meaningless question, and is thus an apt metaphor for the meaningless of existence. Why are we here? Because! Just because! As the philosopher Soren Kierkegaard asked in his Journals: "What is the Absurd? It is, as may quite easily be seen, that I, a rational being, must act in a case where my reason, my powers of reflection, tell me: you can just as well do the one thing as the other, that is to say where my reason and reflection say: you cannot act and yet here is where I have to act... The Absurd, or to act by virtue of the absurd, is to act upon faith ... I must act, but reflection has closed the road so I take one of the possibilities and say: This is what I do, I cannot do otherwise because I am brought to a standstill by my powers of reflection."

The Kiwi equivalent is a sort of half-arsed shrug of the shoulders and a "she'll be right" - which I think Rob manages rather well in his use of objets trouvé. There is a sense in which he is trying to find order and meaning in a chaos of found and variously emotionally or memory-charged objects and materials, and when that can't be found, one can only respond with a joke. In his 1956 short story "Jokester," Isaac Asimov has one of his characters say, rather irritably, "Science has advanced to the point where the only meaningful questions left are the ridiculous ones. The sensible ones have been thought of, asked and answered long ago." - well this is Rob trying to answer an un-ask-able and unanswerable and utterly ridiculous question. One suspects though, that like Douglas Adams' ultimate meaning of life, the universe, and everything, the question and the answer cannot both exist in the same universe.

But that's OK. Rob is a pragmatic ironist in manner described by the late philosopher Richard Rorty. All language and signs are contingent. We may never approach the ultimate truth - and that ultimate truth may not be approachable, or even exist - but that's cool, because the important thing to focus on is the journey there.

In 1938 Dutch historian and cultural theorist Johan Huizinga (hoy-zing-ah) published the book Homo Ludens - "game playing man" - outlining the importance of the play element of culture and society. Huizinga uses the term "Play Theory" to define the conceptual space in which play occurs. Huizinga suggests that play is an essential, though insufficient condition for the generation of culture.

Huizinga says "Wherever there is a catch-word ending in -ism we are hot on the tracks of a play-community." What sphere of human endeavour is more fraught with isms than the arts. Huizinga cites the "architect, the sculptor, the painter, draughtsman, ceramist, and decorative artist" who in spite of her/his "creative impulse" is ruled by the discipline, "always subjected to the skill and proficiency of the forming hand." Aside from the making of art, the other part of the game is the way art is received by the public - a struggle for currency between the old ism and the new ism.

Rob is definitely a forming hand between old and new -isms, and his brand of concrete humour is frequently a metaphor for existentialism. It is perhaps less about the formal aesthetics of Marcel Duchamp, than it is about the heavily symbolic, abject and transitional materials of Joseph Beuys and Mike Kelley. A bucket balanced on a pole is intrinsically symbolic of the fragility of existence - the memento mori or vanitas. It becomes even more meaningful in a Christchurch randomly struck by aftershocks. It's also funny, quaint, and absurd, but that takes nothing away from its seriousness.

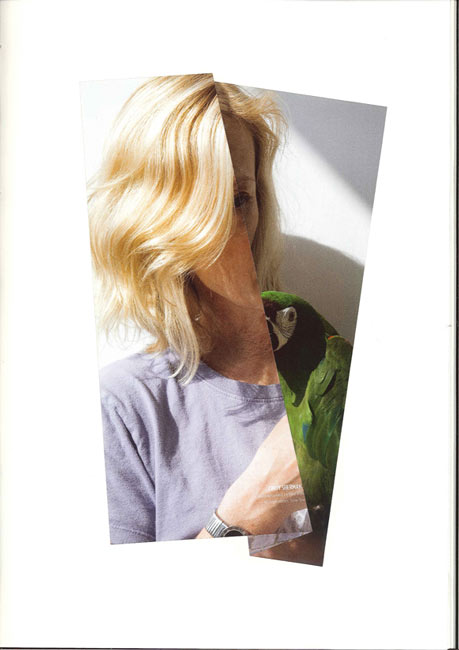

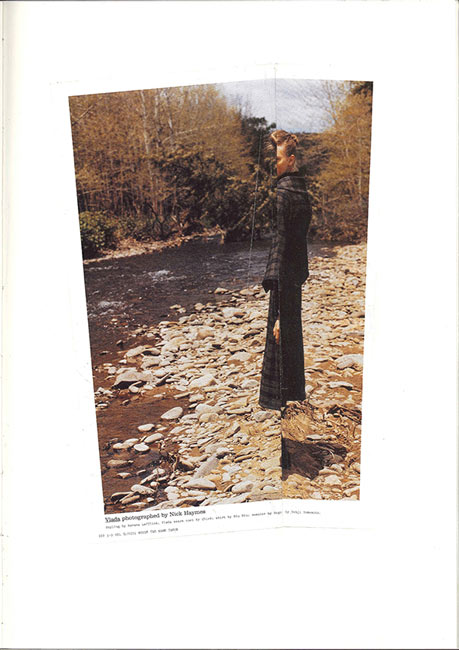

The Cyclops prints likewise hinge on a gentle, uncluttered humour. They are sculptural in that they have been created from a single image folded so as to distort it in such a way as to render the subject a Cyclops. There is a conscious reference to, and subversion of the classical myth of the Cyplopes - a race of giants who created Poseidon's trident, Artemis's bow, Zeus's lightning, and other hero weapons and tools. They were said to have brute size and strength, and are credited with massive masonry such as megalithic observatories. Their single eye makes them a metaphor for the artists - the all devouring gaze.

Of course, one might also elaborate from this a reference to the One Eyed Cantabrian. Certainly Rob isn't above the occasional lame pun or practical joke - such as the cast metal brick that weighs more than a real, already heavy brick would. There is a direct lineage going all the way back to the Book of Genesis. God puts this tree in Eden and by forbidding Adam and Eve to eat the fruit from it, deliberately puts the suggestion in their minds - the first practical joke. We are deceived, our weakness and vanity played upon. We are tempted to pick up the brick, deceived by the Trompe-l'il mimesis - and may possibly strain something in the act. It's the flip side of Existential Absurdism - Gnostic Manichaeism: the created universe as a cruel joke. That would make humanity the punch line.

But yes. Rob is a voracious eye with an appetite for mundane details - and these details, without fuss or elaboration, he makes triumphant and fascinating by simply re-arranging their elements to achieve the most aesthetically satisfying and logically meaningful solution to the problem of objects in space. It is the poetic dolour, and sometimes delight of mundane, quidditic banalities. That is what I think Rob's

process is. He observes. He is like Autolycus in Shakespeare's A Winter's Tale - "a snapper up of unconsidered trifles". The most humdrum, ubiquitous, mundane things he sees are transformed into aesthetically and conceptually fascinating aggregates. With most installation artists it tends to be either the one or the other - not both. That fact alone makes Robert one of the most interesting emerging artists practising in New Zealand today."

APW